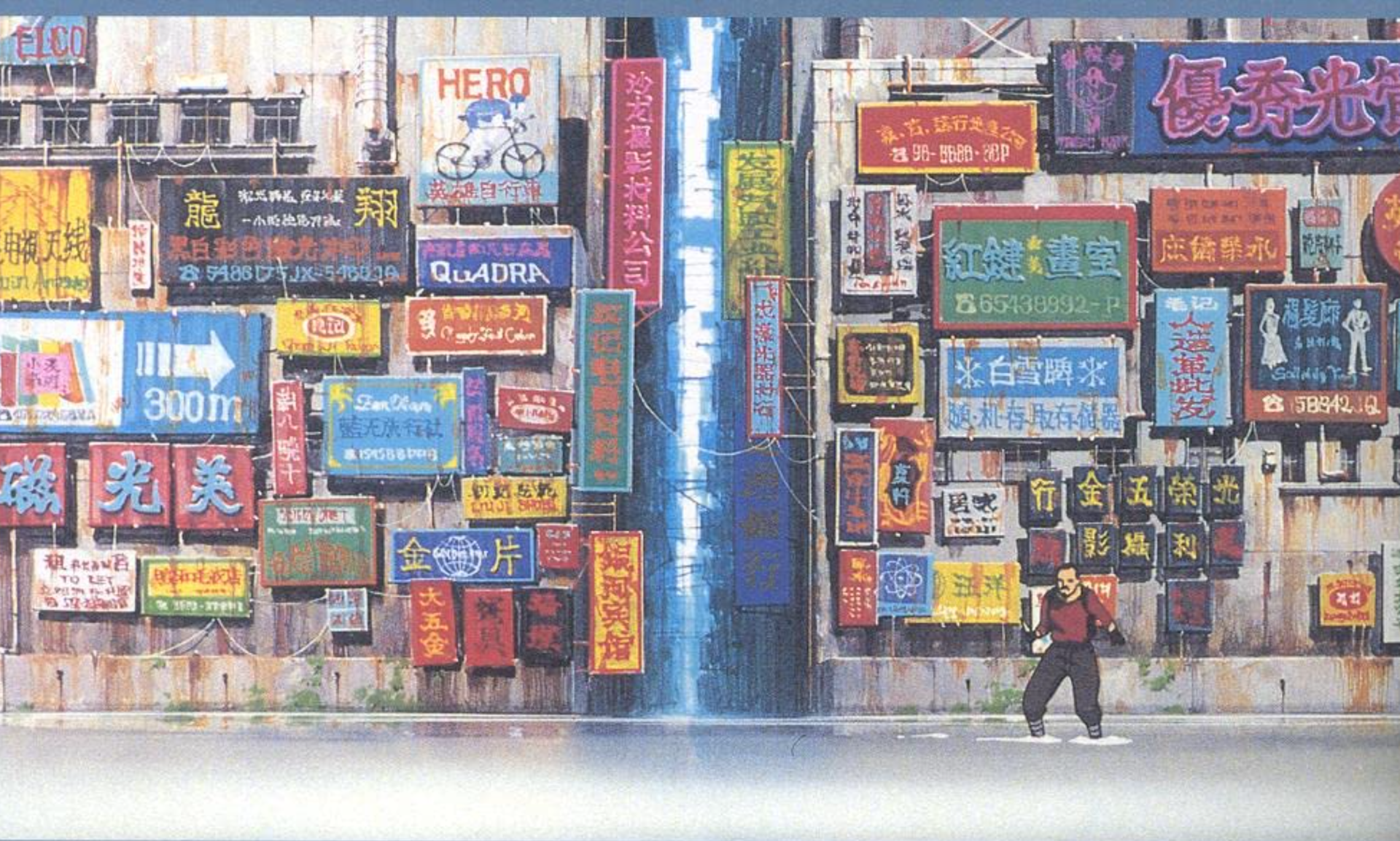

Ghost in the Shell (1995) Directed by Mamoru Oshii

Orientalism grapples with problematic depictions, scholarship, and narratives about regions and cultures in the East. The word Orientalism and the negative way it is understood today comes from Palestinian scholar Edward Siad’s 1978 book ‘Orientalism’. Colonial expansion into the East led to European imperialism instilling Western ideas of superiority, viewing Asia as a mystical and exotic land. Siad argues Orientalism serves as a colonial categorisation of ideas, styles, people, and places, functioning as an ideological arm of imperialism by othering and lumping together. (Siad, 1978:32) Operating from a place of economic European superiority and power, Orientalists helped construct and strengthen problematic, inaccurate, and condescending narratives of the East. When Orientalist and colonialist narratives define the East as ‘other’ we simultaneously define ‘we’, the West as superior. Fusing large and diverse areas of the world into one cultural entity, the ‘Orient’ exists because “the West needs it; to bring the project of the West into focus.” (Morley & Robins, 1995:155) The Orientalist rhetoric contributed to a dichotomising world view, portrayal and distinction between East and West. The ‘Orient’ was exotified in various positive and negative ways. People of the region were often described as primitive, undemocratic, and irrational. (Siad, 1978:85)

Techno-Orientalism imagines Asia and Asians in hype-technological terms in literary, cinematic, and new media representations.” (Nui G, Roh D, Huang B, 2015:2) Techno-Orientalism fuses technology and Orientalist ideas depicting an Asian influenced future. The West manipulates and appropriates the ‘orient’ to strengthen their own cultural identity “Techno-Orientalism defines the images and models of information capitalism; the Orientalism of cyber society and the information age, aimed at maintaining stable identity in a technological environment.” (Ueno, 1999:95) Techno-Orientalism imagines what Asian prejudice looks like in the future economically and culturally. The “techno” refers to economic globalisation and the formation of temporal asymmetry: “an Asianness characterised by the juxtaposition of cultural retrograde with technical hyper-advancement” (Nui, Roh, Huang, 2015, p.7) A colonialist perspective is a bedrock for prejudice that underlines the genre: a futurist dystopian world where the dominant economic East serves as an antagonist to the economic West.

The imagined Asiasnised future has become more prevalent in pop culture across movies, music and video games following the globalisation of media products in the wake of neoliberal trade politics and the flow of information and capital between the East and West. (Nui G, Roh D, Huang B, 2015:2) Techno-Orientalist entertainment was popularised in the 1980s due to Western fears of Japan’s economic success. Japanese companies Sony and Matsushita bought out well-known American companies such as Columbia Pictures, CBS records and MCA universal. These events triggered worries of Japanese domination and ‘Yellow Peril’ - referring to Western fears of East Asians taking over and corrupting Western society. (Yoshimi, 1999:45) The rise of Japan as an economic superpower and its rapid modernisation threatened Western pride and superiority.

Blade Runner (1982) Directed by Ridley Scott - Poster and geisha

Cyberpunk cinema is a genre within Techno-Orientalism that employs tropes and archetypes that contribute to a nuanced form of prejudice in Western-made films. Techno-Orientalism focuses on the global future “while Orientalism defines a modern West by producing an oppositional and pre-modern East, Techno-Orientalism symmetrically yet contradictorily completes this project by creating a collective, futurist Asia to further affirm the Wests centrality.” (Nui, Roh, Huang, 2015, p.7) A signifying trope in the genre is the ‘high tech, vaguely Asian-coded dystopia’. Typically, a city in an unspecified country influenced by non-specific Asian cultures, collective future Asia, maintains Western supremacy. The cyberpunk genre prepares a fetishising gaze upon Japan as a “seductive and contradictory place of futuristic innovation and ancient mystique.” (Nui G, Roh D, Huang B, 2015:6) The cyberpunk film Blade Runner (1982) portrays a well-known image of Japan paradoxically combining the traditionalism of the samurai and geisha with high technology. Depicting a densely packed city of Asian extras, Japanese advertisements including a billboard of a geisha. (Kogure, 2006:40)

Cloud Atlas (2012) Directed by Tom Tykwer, Lana Wachowski, Lilly Wachowski

Another trope of Techno-Orientalism is the ‘automaton cyborg archetype’ almost always played by a vaguely Asian character. This trope perpetuates negative constructions of the Asian body, which is typically a labourer machine, which upholds model minority stereotypes. (Wong, 2017:106) There is clear xenophobia in the cyberpunk genre depicting Asians as emotionless, mechanised beings and Asian cityscapes as grimy and corrupt landscapes. A female cyborg typically exists inside a fetishised, sexually subservient body that is eventually violently dismembered, occurring only after the Asian cyborg threatens to breach white superiority. The hyper-sexualised, obedient woman can be seen in the examples of Sonmi-451 from Cloud Atlas (2012) and Kyoko from ‘Ex Machina’ (2014). Sonmi-451 is a fabricant, a manufactured human-like clone made to fulfil the needs of consumers which are humans known as ‘Pure Bloods’. Working as a waitress she and many clones alike are subject to harassment and abuse from customers, unable to defend themselves. (Park, 2018:21) Techno-Orientalist Asian cyborgs are reduced to emotionless machines, thus Asians are dehumanised and shown as mechanical objects. Kyoko’s role is similar; A maidservant programmed to tend to the desires of her creator Nathan Bateman. Kyoto is controlled and frequently abused by Nathan; used as a domestic sex slave and is unable to speak or understand English. (Park, 2018:21) Asians are often depicted as an all-knowing, ominous, force that is hyper mechanised or shown as weak and needing to be rescued by the protagonist. In future worlds where technology is cable of replacing biological bodies with synthetic ones, “we learn which bodies attain subjecthood and which are destined to be used and discarded” (Nishime, 2017:23)

Kyoko - female cyborg

Ex Machina (2014) Directed by Alex Garland

Although Techno-Orientalism rose to popularity in the 80s due to ‘Yellow Peril’, Japanese creatives have adopted Techno-Orientalist ideas to fit narratives in science fiction media. The 1995 animated classic ‘Ghost in the Shell' turns this trope on its head. Masamune Shirow’s ‘Ghost in the Shell’ was originally published in 1989 as a manga series with an anime adaptation, and more recently a live-action Hollywood film. Featuring a strong Japanese female cyborg protagonist that has agency in her decisions against a cast of weaker male characters. Motoko Kusanagi embraces her cybernetic aspects and contemplates the post-human body’s relationship between machine, identity and healing. Techno-Orientalist tropes have been redefined in another nationalist context, further demonstrating its “discursive hegemony as it serves a site other than its point of origin”. (Nui G, Roh D, Huang B, 2015:8)

Ghost in the Shell (1995) Directed by Mamoru Oshii

Techno-Orientalism offers the opportunity for critical reappropriation, proposing a counter-dialogue of Asian images in cultural and political contexts. Korean artist Nam-June Paik had a uniquely global view concerned with cultural and technological fluidity, employing Techno-Orientalist tropes in art envisioning a united world. (Park, C 2015:211) The dehumanisation of Asian people and appropriation of Asian culture used in the design of dystopian future worlds and characters in Techno-Orientalist media perpetuates negative stereotypes about the Asian community and must be recognised as xenophobia.

Artist Nam June Paik Predicted the Future

References

Kogure, S 2006, ‘Othering around technology: Techno-Orientalism, Techno-Nationalism, and identity formation of Japanese college students in the United States’

Morley, D and Robins, K, 1995, Spaces of Identity: Global Media, Electronic Landscapes and Cultural Boundaries. London: Routledge 130-199

Nishime, L, 2017 ‘Whitewashing Yellow Futures in Ex Machina, Cloud Atlas, and Advantageous. Journal of Asian American Studies 20.1 : 29–49.

Nui G, Roh D, Huang B, 2015, Techno-Orientalism: Imagining Asia in Speculative Fiction, History, and Media 2015, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick.

Park, C. 2015. 15. A Poor Man from a Poor Country: Nam June Paik, TV-Buddha, and the Techno-Orientalist Lens. In: Roh, D., Huang, B. and Niu, G. ed. Techno-Orientalism: Imagining Asia in Speculative Fiction, History, and Media. Ithaca, NY: Rutgers University Press, pp. 209-220. https://doi.org/10.36019/9780813570655-017

Park, H 2018, ‘Representing Seoul: Techno-Orientalism and the Future of Reproduction in Cloud Atlas’, Wasafiri, vol. 33, no. 4, pp. 20–26

Said, EW, 1979, Orientalism First Vintage Books edition., Vintage Books, New York. pp.1-408

Ueno, T 1999, ‘Techno-Orientalism and media-tribalism: On Japanese animation and rave culture’, Third text, vol. 13, no. 47, pp. 95–106.

Wong, D, 2017, Inorganic Asian North American Lives: Virtual Dismemberments, copies and wellbeing, English and Cultural Studies, McMaster University, Canada pp. 1-255

Yoshimi, S “’Made in Japan’: The Cultural Politics of 'Home Electrification' in

Postwar Japan,” Media, Culture and Society 21:2 (1999), 149-171.